Source: Penn State Extension

Corn planted into standing un-rolled cover may show reduced yields due to lower populations and greater plant height variability.

Save For Later Print

The practice of planting a cash crop into a living cover crop is still is in its infancy. Fortunately, we’ve had the opportunity to learn from many early adopters of this practice. However, as this practice has become more commonplace some producers have had less than desirable results.

Early research on the practice often utilized a front mounted roller-crimper and more recently planter-mounted roller-crimpers have been used to roll covers ahead of the planting operation. Some of the issues we’ve observed in planting green were with farms that planted corn into a standing small grain cover. The causes for not rolling may include letting a fast growing cover crop get away from someone or overconfidence in planting green without knowing the limitations of the practice. In 2017, Extension educators surveyed fields that were planted green to see what may be the cause of some of these issues and here is a summary of some of our observations:

Planting into un-rolled covers may reduce populations. In the few locations where un-rolled areas could be compared to rolled or bare areas, lower populations were present, which can often correspond to a yield reductions. The loss could be from competition and shading of the emerged seedlings or inconsistent planting conditions due to the cover.

Observation Rolled Not rolled

Population (thousands) 32.8 28.8

Plant height (in) 18.0 21.6

Plant height deviation (in) 2.8 4.1

Data recorded from a site in Somerset County where a portion of the field was rolled with a cultipacker prior to planting and a portion was not. The portion that was rolled had higher populations and lower plant-to-plant height differences. Plants in non-rolled areas exhibited more of a “spindly” appearance with taller plants and smaller stems.

Stands planted into un-rolled cover were more variable. In Somerset County where a rolled portion of a field was compared to an un-rolled portion, plants in the un-rolled area had greater variability in height which may be due to shading from the standing cover crop providing uneven light to emerging plants. This variability can negatively impact yield as taller plants out-compete shorter plants for light and nutrients, reducing the per-plant yield of the shorter plants. Also observed in multiple locations of un-rolled cover were corn plants that were taller but with thinner stems. These spindly plants may have been pushing vertical growth at the cost of developing a thicker stalk in order to get over the standing cover.

Planting green into un-rolled cover may result in less than desired populations and intra-plant competition due to differences in plant heights. For instance, the plants on the right may out-compete the plants on the left to the point where they may not make an ear.

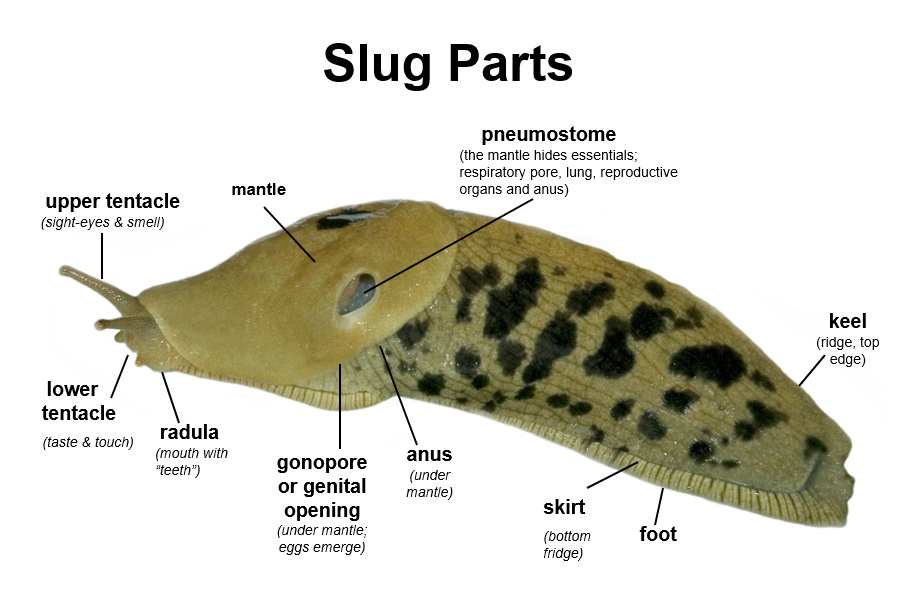

Slugs are still a problem. Although research has been promising for utilizing planting green techniques to reduce slug damage, results are not guaranteed. Planting green is thought to be a means of reducing slug pressure as cereal grain cover crops provide an alternate food source to slugs rather than an emerging corn or soybean cash crop. Rolled cover can also provide protection for natural predators of slugs. In 2017, slug damage was variable in planted green fields with sites in Lancaster and Cambria showing slug feeding, with one requiring replanting and having slug damage to the replanted crop.

Based on observations from 2017 and lessons learned from now veterans to the practice of planting green, I suggest the following when considering adapting planting green on your farm.

Plant corn only if you can roll. Based on the observations of reduced populations, height variability and spindly plants, utilizing a roller-crimper when planting green is likely the best method to guarantee success. Planter-mounted units will likely become the most common method of rolling due to ease of use and limited setup time. However, if you’re looking to dabble in a few acres using a cultitpacker to roll cover is still an option; just be sure to roll in the direction of planting to reduce hairpinning and wrapping of residue around the planter.

At this point in time we do not know at what height rolling is not required. Early observations suggested that competition from standing cover was not an issue when cover crops are less than 16 inches tall. However, there are some indications that 12 inches of standing cover may negatively impact emerging plants. At this time, one is likely better off using a roller-crimper until there is more information on how termination heights affect corn emergence or how legumes or other short-growing cover crops affect corn stands.

If you are unable to roll cover crops, soybeans may be better when planting into un-rolled covers as they can better compensate for reduced populations and inconsistent plant heights. Recent research performed at multiple locations by Penn State showed that there was no difference in soybean yields between stands planted green and those planted into bare or early-terminated, which demonstrates that soybeans are less impacted when planted into more variable conditions.

By exposing the emerging crop to even light from a rolled cover, plants have a greater opportunity to emerge and establish at the same rate, resulting in a more uniform stand. Meanwhile the rolled cover will help to conserve moisture and buffer soil temperatures throughout the growing season.

Start simple. If you’re modifying equipment for planting green, simpler is better. Smooth row cleaners are an excellent start as they reduce wrapping and open a furrow for the seed. Coulters should be removed if possible to eliminate another potential wrapping point and place more weight on row units and rollers. Smooth or shorter spiked closing wheels are a good starting point, especially if guards can be installed to keep residue away from them. Fertilizer applied behind the closing wheels is another practice that has been shown to work well. Once you get a feel for how your equipment behaves under your conditions, refinements can be made based on your needs.

Adjust your cover crop rates. Planting cover crops at rates traditionally used for harvesting small grain are not necessary when planting green. Small grains can produce large amounts of biomass at lower planting rates due to tillering and manure application or early planting can also increase cover crop biomass. However, high levels of biomass can be difficult to deal with come planting (green) time. To ensure that you’re not growing more material than you can handle, start at cover crop seeding rates that are half of typical recommendations. This means that small grains should be planted at 1 bu/ac or less, although one should be aware that seed size can varies greatly which ultimately affects the number of plants per acre.

Select the right hybrids. In general, no-tillers should purchase hybrids that have good seedling vigor and rooting and the advice holds true when planting green. With the right hybrid seeding rates may not need to be increased when planting green. Ideally, one should measure emerged populations and compare to historical numbers or with fields that are not planted green before committing to higher seeding rates. Increased populations for soybeans may also not be necessary as soybeans can tolerate lower populations with no impact to yields.

Be prepared for the nitrogen penalty. As small grain cover crops mature, the amount of carbon relative to nitrogen increases, which means that nitrogen needs to be removed from the soil for the residue to decompose and the timing of this can negatively impact the growing cash crop.

Those planting green have seen success in applying 50 lbs. of nitrogen at planting to promote residue breakdown and provide available nitrogen as the corn begins to grow. Those with frequently manured systems may find that extra nitrogen is not necessary and with legume cover crops additional nitrogen is not typically required at planting.

Although we’re far from having a 100% understanding of planting green, we’re learning how to better refine the process each year through research and observations of the early adopters of this process. If you’re looking to plant green for the first time I suggest that you seek out those early adopters and see what they’ve learned from the practice. Knowing the limitations of planting green will better ensure that you’re using the right tool in the right scenario.